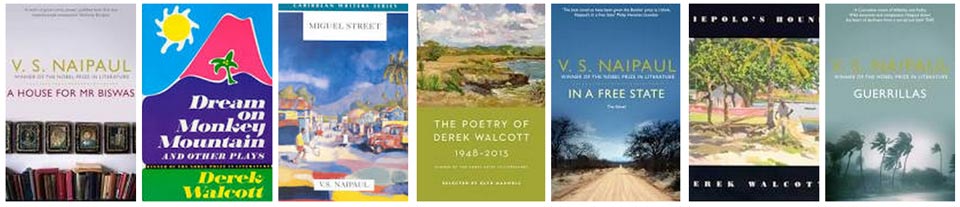

The Caribbean has produced two Nobel Prize laureates in literature in the persons of Sir. VS Naipaul (2001), and Derek Walcott (1992). Two opposite figures but equally brilliant craftsmen. The first infamous for denying his Caribbean roots. When he won the Nobel Prize, he only thanked India, the land of his parents, and Britain, though he was born in Trinidad. His masterpiece, A House for Mr. Biswas, probably would not have been conceived without his Caribbean experience. On the other hand, Derek Walcott has been outspoken about his Caribbean Creole reality as a cradle for creativity and genius. In his poetic odyssey, Omeros, a modern masterpiece of English literature, he narrates the ancient story of Homer's travels, from a Caribbean perspective.

In our Euro-centered educational system, on the island of Curaçao, there was no room for more in-depth or, in some cases, even a superficial reading of these great masters, not to mention other writers of the region.

Although VS Naipaul was introduced in English class, there was no mention of Derek Walcott's earlier work. I had French for four years but never once was Césaire or Glissant mentioned. However, at school I had the fortune of learning with Jopi Hart, an excellent English teacher, up to this day an illustrious man of letters and a well-informed social critic.

Meneer Hart instilled an enduring love of literature in me. He taught in such a way that writings came alive, sending me gasping for air down a path of fantasy and imagination to a paradise of words, colors, smells and images, where pain and teenage angst, could find a home.

In Dutch literature class, great authors of the Antilles like Cola Debrot, Boeli Van Leeuwen, and Frank Martinus Arion were touched upon, and we had to select from their works for our reading list. But we missed the chance to make a make a more thorough use of regional literary works in our education. However, we did learn critical thinking, thanks to teaching giants like a Jopi Hart and a Sally Pieters, our Spanish teacher.

Papiamento, my creole mother tongue, was not a subject in school. That has changed, and our children have the chance to study their literature, in their language. Greats like Pierre Lauffer, Luis Daal, and Joseph Sickman Corsen are speaking to the younger generation. Regretfully, it is not the case in other parts of the Caribbean, where obstinate gatekeepers prevent creole language users from formally analyzing their literary expressions. Take the case of the French-based Creoles of the French Antilles and Guyana, where unlike Haiti, the Creole is often not accepted for official Scripture use, or in the school system, alongside French. However, for example, written and audio renditions of the translations of gospel narratives in the creoles of Jamaica, Belize, Suriname and Haiti witness to the beauty of these tongues.

We can be grateful for teachers like Jopi Hart, linguists like the late Enrique Muller, for Martha Dijkhoff, and Sidney Joubert. For translators and poets like Lucille Berry-Haseth, and many others like Antoine Maduro, one of the founding fathers of Papiamentu linguistics. In my personal journey, my fellow Papiamentu Bible translators, the late Fluvia Wagner, and Shirley Henriquez deserve special mention. Indeed, thank God for all Bible translators across the Caribbean basin.

We do not want to stop speaking English, Dutch, Spanish and French. But the days that our Creoles, were rejected, downtrodden and scorned, should be definitely behind us.

I salute all teachers, language enthusiasts, poets, and songwriters, who keep their languages alive. From the coasts of Central America to the watery land of the Guyana's, from the hilly island of Cuba to the ABC islands of my birth, from San Andres to Jamaica, to Haiti.

I salute our present and past storytellers from the Bahamas down across the chain of pearls that are the Greater and Lesser Antilles, who have forged something new out of the often violent clash of humiliating encounters.

We should fight for our Caribbean languages and literature, including our unique Creoles, and not rob ourselves of our treasure.

Read also our Main Story: Nostalgia (A poem by Enrique Muller from Libra)

By Marlon Winedt

Marlon studied in the United States and in the Netherlands in the areas of theology, philosophy, linguistics and Bible translation. He was one of the translators of the Beibel Papiamentu Koriente (1997). Subsequently, as a Global Translation Advisor with the United Bible Societies, he has been involved in Bible translation for a total of nearly 25 years now, both in training on a global level and guiding projects in the Americas and Caribbean region, while capacitating pastors and church leaders. He has written different articles in English, Spanish and Dutch on academic topics related to exegesis and translation, while co-authoring a book on the prophet Micah in Spanish.

He and his wife Sandra have three children and live on the island of Curaçao, where he is a member of the team of pastors of Iglesia Bida Nobo, Assemblies of God; he is an international teacher and conference speaker across denominational divides. He is an adjunct professor with Global University, Missouri, and has varying academic and board level commitments with seminaries in Suriname, South Africa, and Venezuela.

Visit his site: "United Bible Societies".